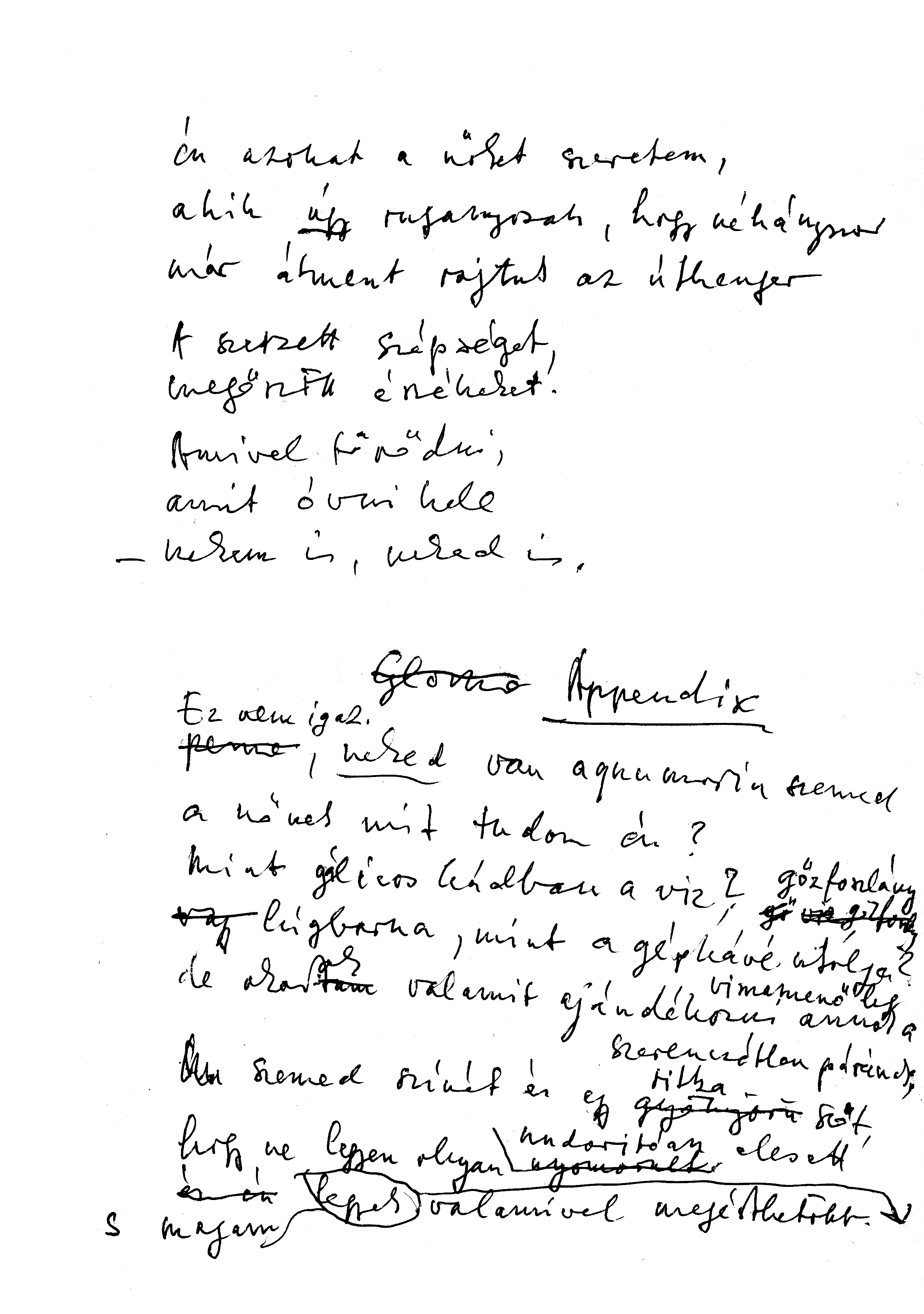

![]() To reach the sunlit path...

To reach the sunlit path...

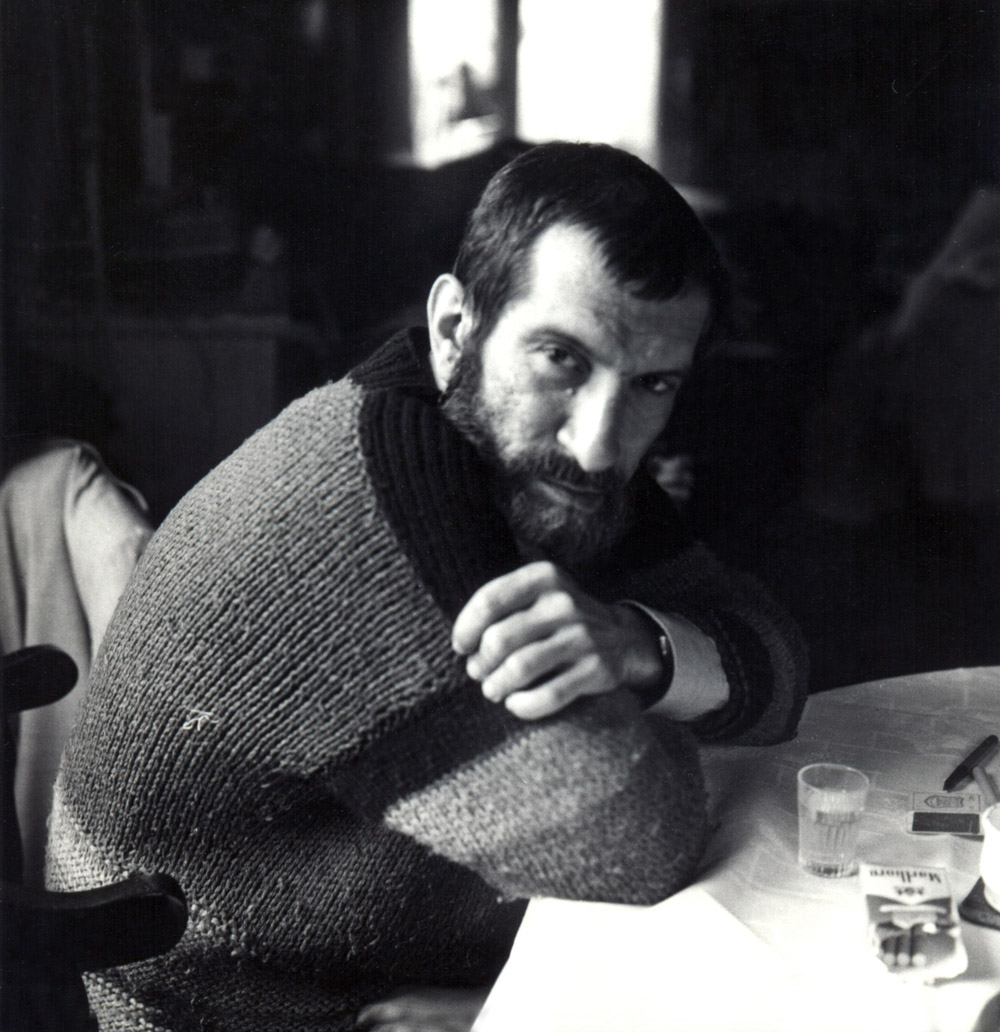

Petri György (Budapest, december 22., 1943. – Budapest, july 16., 2000.) Kossuth and József Attila-prize winner hungarian poet, translator and journalist.

To reach the sunlit path...

It began as an ordinary summer night.

I walked from one tavern to another.

Perhaps I was drinking in the Nylon pub,

close to the suburban railway terminal at the Margaret bridge, (or had it been torn down by then?).

I do not know, or I might have been on Boraros square.

Those walks always asted until morning or just for two days, and led to anywhere.

Anyway, I was sitting somewhere drinking.

(Then drinking anything: tasting youth.)

I was not yet reading in taverns,

no, no, not yet burying myself

into a book or a magazine, not staring at the tabletop.

I was not yet irritated when somebody addressed me.

"Would you pay a drink for me?" asked a hoarse smoke-tuned voice of a woman behind me. It was a young voice.

"Order one" I said, turning toward her. A woman around fifty stood diagonally behind me. Adherent,

dandruff hair that had used to be light brown;

toothless gums, chapped lips, bloodshot

aquamarine eyes,* yellowed white synthetic sweater,

brown pants, white beach shoes found in the garbage.

She ordered a shot glass of mixed liquor and a small cup of beer. I didn't argue about her taste. "I’ll go with you for twenty" she said. I was surprised. The price -- for a price -- was absurdly low (even then). I knew the rates of streetwalkers of Rakoczi square. Twenty forints was not a price. On the other hand, the woman wouldn't have stood up to scrutiny on the Rakoczi square, in fact, on any field. It would have been logical that if she wanted something, she would pay.

But much more. And she wanted.

"Come, I want it" she said "I badly need it."

Never could I hurt a woman in her femininity

(unless it specifically was my goal).

But that ... I went; I felt: I had to.

After all, I was haunted and confused

like stirred up mud at the time and

only in those “espressos'' and “buffets''

I could feel some false superiority

among the true afflicted of deprivation and homelessness.

She dragged me along a long street for a long time, clinging to me. It was embarrassing, but a necessary part of the payment. I embraced her; we ended up in a basement: we might have gone down a lot of stairs

in some no one knows from where coming half-glow.

The bed. A litter thrown together with some clumped batting. She didn't strip, only loosened and pushed down her pants.`This is my usual way when I screw in the bush'

said jokingly. It was not against me, myself did it only to the most necessary extent and I threw off my jacket too

- it should rather be filthy than wrinkled.

"Kiss me." Yes, it was unavoidable.

She had rancid foul breath and scaly lips, her tongue

and palate were dry just like an empty sardine can

in which my tongue searched -- anon the sharp edges could scratch it. I was terrified that I would throw up in her mouth, and because of that there came a laughing attack, my tears were flowing on her rough skin until

I became a master of my peristalsis. Her pussy

was tight and dry. Hardly did it stretch, and even less did it get wet. "Hold on" she said and her fingers dug into

a margarine that she already had begun to consume; she stuffed a dose into herself, and then one more dose again. (Is she going to EAT from this later?)

"Can I wash myself somewhere?" I asked later.

She showed to a tube stub. The water ejected,

my pants became completely sloppy like I had pissed myself. "That belongs to it too" I murmured. I still had a fifty-forint banknote. She shook her head, "I said

that I need twenty, and it's not the price. I wanted the thing and I simply need twenty forints."

"Then give back thirty," I said, "I don't have a twenty-forint note." "You are stupid" she said, "If I could give back thirty, I shouldn't need your twenty" said logically.

And the next moment she fell asleep with an open mouth.

I shrugged my shoulders (`if you're so proud'),

pocketed the fifty note, found my jacket,

and stumbled up the stairs.

To reach the sunlit path,

where my beige dress and white shirt light up;

up the chipped stairs to purity,

where wind blows and white foam sizzles,

grimly absolve, indifferently threaten;

stairs of nausea, minus-floors not wanting to run out,

summer dawn, nine hundred and sixty-one.

*Bullshit. You have aquamarine eyes. And hers? I don't know. As water mixed with copper-sulfate in a tub? I just want to present something to that unfortunate creature, say, the color of your eyes and a rare word so that she be not as disgustingly afflicted. And I myself be somewhat more comprehensible.

Hogy elérjek a napsütötte sávig…

Szokványos nyári éjszakának indult.

Sétáltam kocsmáról kocsmára.

Talán éppen a Nylonban ittam,

a HÉV-végállomás mellett, a Margit hídnál

(vagy azt akkor már lebontották?).

Nem tudom, lehet, hogy a Boráros téren.

Ezek a séták mindig reggelig vagy épp két napig tartottak, és akárhová vezettek.

Mindenesetre, valahol ültem, ittam.

(Akkor még akármit - kostolódó ifjúság.)

Még nem olvastam a kocsmákban,

nem, nem, még nem temetkeztem

könyvbe-újságba, nem fixíroztam az asztal lapját. Még nem idegesített fel, ha szóltak hozzám.

"Fizetsz valamit?" kérdezte egy dohánykarcos

női hang a hátam mögül. Fiatal hang volt.

"Kérjél" - mondtam felé fordulva. Ötven

körüli nő állt rézsút mögöttem. Letapadt,

koszmós, egykor világosbarna haj;

beroskadt íny, cserepes ajkak, vérágas

kötőhártya, aquamarin szemek*,

megsárgult, fehér műszálas pulóver,

barna nadrág, szemétben talált fehér strandcipő.

Kevertet kért és sört, pikolót. Ízlését nem vitattam.

"Eljövök egy huszasért" - mondta. Ezen meglepődtem.

Az ár - árnak - képtelenül alacsony volt (már akkor is).

Ismertem a Rákóczi téri kurzust. Húsz forint az nem ár.

Másrészt a nő nem állta volna meg a helyét

a Rákóczi téren, sőt semmilyen téren.

Az lett volna a logikus, hogy ha akar valamit, ő fizet.

De sokkal többet. Márpedig akart.

"Gyere, akarom" - mondta -, "nagyon szeretnék."

Soha nőt nőiességében megbántani nem tudtam

(hacsak nem kifejezetten ez volt a célom).

No de hogy... Mentem; úgy éreztem: muszáj.

Hiszen űzött voltam és zavaros, mint a fölkavart iszap akkoriban, és sak ezekben az "Eszpresszókban", "Büfékben" érezhettem némi álfölényt nélkülözés és hajléktalanság valódi nyomorultjai között.

Sokáig vonszolt egy hosszú utcán, hozzám bújt.

Ez kínos volt, de szerves része a törlesztésnek.

Átöleltem, egy pincében kötöttünk ki, nagyon sok lépcsőt

mehettünk lefelé valami nem tudni honnan

derengésfélében. Az ágy. Befilcesedett vatelindarabokból összekotort alom. Nem vetkőzött, csak megoldotta, lejjebb tolta magáról a nadrágját.

"Így szoktam meg, ha bokor alatt dugok" - mondta közvetlenül. Nem volt ellenemre, magam is csak a legszükségesebb mértékben, meg a zakómat dobtam le

- inkább legyen koszos, mint gyűrött.

"Csókolj meg." Hát igen, ez elkerülhetetlen.

Avas szájszaga volt, ajka pikkelyes, nyelve,

szájpadlása száraz, mintha egy üres szardíniásdobozban

kotorászna a nyelvem - mindjárt fölvérzi az éles perem.

Rettegtem, hogy menten a szájába hányok,

ettől viszont röhöghetnékem támadt,

ömlöttek durva bőrére a könnyeim, amíg

ura lettem a perisztaltikának. A lába köze

szűk, száraz. Alig tágul, alig se nedvesedik.

"Várjál" - mondta, és belevájt ujjaival

egy megkezdett margarinba, magába maszírozta,

aztán még egy adagot.

"ENNI is fog még ebből?"

"Meg tudom mosni valahol magam?" - kérdeztem később.

Egy csőcsonkra mutatott. A víz kilövellt, merő

lucsok lett a nadrágom, mintha behugyoztam volna.

"Ez is hozzátartozik" - mormoltam. Egy ötvenesem

volt még. A fejét rázta: "Mondtam, hogy egy

huszas, és ez nem az ára. Én akartam, a huszas

meg egyszerűen kell."

"Akkor adj vissza" - mondtam -

"értsd meg, nincs huszasom."

"Hülye vagy" - mondta - "ha vissza tudnék adni ötvenből,

nem kéne a huszasod" - mondta logikusan.

És a következő pillanatban elaludt nyitott szájjal.

Vállat vontam. ("ha ilyen büszke vagy"),

zsebre gyűrtem az ötvenest, megtaláltam a zakóm,

és botorkáltam fel a lépcsőn.

Hogy elérjek a napsütötte sávig,

hol drapp ruhám, fehér ingem világít,

csorba lépcsőkön föl a tisztaságig,

oda, hol szél zúg, fehér tajték sistereg,

komoran feloldoz, közömbösen fenyeget,

émelygés lépcsei, fogyni nem akaró mínusz-emeletek,

nyári hajnal, kilencszázhatvanegy.

*Hülyeség. Aquamarin szemed neked van. A nőnek? Mit tudom én. Mint gálicos kádban a víz? Csak akarok valamit ajándékozni annak a szerencsétlen párának, mondjuk a szemed színét, meg egy ritka szót, hogy ne legyen olyan undorítóan elesett, magam pedig legyek valamivel megérthetőbb.

To reach the sunlit path...

To reach the sunlit path...